The first story which I wrote and submitted was for the 1984 New Straits Times Short Story Competition. It was called Miel and the Honey Bunch or something pretentious-sounding like that. The exact story and wording are all gone now. Success came to me early as a writer, to my detriment, as I since then I always thought I would be a professional and successful writer without much effort. I developed a complacency towards the creative act of writing.

I was then 14 years old and the youngest entrant. There was no such thing as YA genre at the time. You were either an adult or a child. I didn’t get a mention and didn’t win anything. I competed as an adult but any competition was as tough then as it is now. Out of hundreds and maybe thousands of entries, there can only be one winner and the rest runners up or in the commended list. I was fine. I remember thinking that I just wanted to send it out, no matter what.

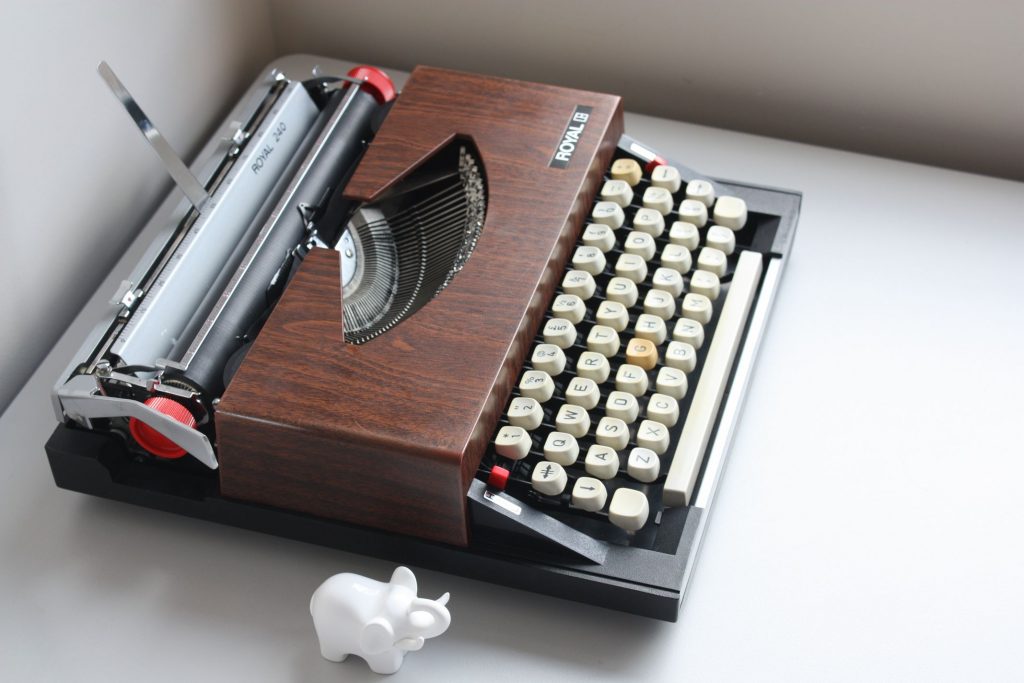

In 1986 I entered the same competition again. I was now 16. As per two years before, I wrote the story by hand and dictated it to my mother who typed the story up in triplicate on this typewriter pictured, the Royal 240. My dad bought it in the Johor Bahru NAAFI in 1970*. It was attractively wood-panelled. It had red and black ribbons. I remember that distinctive strong fresh chemical smell of the typewriter ink. It had two discoloured or stained keys, I am not sure why. Graphic designers? Anybody? When I saw this photo (which is the same model but it is not the actual typewriter that was used) I noticed that it also had two discoloured keys! Imagine my excitement at the discovery. I could not type and neither could she. She used two fingers and typed out 1,500 to 2,000 words. I sat next to her and read out a paragraph first, where we would edit manually, orally or aurally, then a second reading word by word for it to be typed. It took some time but in those days you have time! Everybody had time! We used and re-used the carbon paper for the triplicate copies until it was transparent, until you could put it against a window and see the view beyond the window, until an abstract pattern was made by layers and lines of juxtaposed and superimposed text which no longer made sense, which no longer could be read legibly.

She was strangely a perfectionist and I did not know it then, I just thought ‘Damn! Mummy’s fussy!’. We quarreled, I sulked, we came back to the typing, we snapped, we sent it off. Now I feel grateful now that my mother was so supportive and meticulous about it too. When the words looked messy or clumsy on the page, she would rip the paper out and crush it into a ball like those cartoon caricatures of writers. And then we would start again. As she typed I remember her correcting my grammar and turns of phrases. ‘Is’ or ‘was’, ‘would be’ or ‘would have been’, she would ask, sometimes to herself, sometimes to me, and we would discuss. The final decision was sometimes hers, sometimes mine and sometimes joint. Letter by letter, word by word, sentence by sentence, my story was typed out.

This time I won a prize of a weekend writing workshop at the New Straits Times headquarters: 31 Jalan Riong, 51000 Kuala Lumpur. I got to meet the amazingly kind and funny writer Robert Raymer, a poet called Jeya and a film critic called Kee Thuan Chye. You must remember that I was born and raised in Johor Bahru where nothing happens and most definitely, nothing exciting. It is like saying you are from Hull. The address and postcode of The New Straits Times office is etched in my memory forever. I referred to the letter until I memorised it. It went everywhere I went. It was more valuable than money or keys. I just had to have it with me. I held it in my hand, my school bag, my drawer until it tore at the creases where it once folded. I do not have it anymore. Sometimes I wish I still have it but maybe it was the right thing after all that it has perished over time. The letter had served its purpose which was to endorse me as a writer when I was still young.

Please pre-order my novel Heart of Glass here.

*The Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI /ˈnæfiː/) is an organisation created by the British government in 1921 to run recreational establishments needed by the British Armed Forces, and to sell goods to servicemen and their families.

Photo credit: The Royal 240 by Steve K of the White Elephant