News has arrived that the Great Artist is nearby. In a matter of hours, he will be in the court of Philip the Fourth. Everyone in the palace has been expecting him for months. The Great Artist had been busy travelling in Europe, painting dignitaries. He will shortly be here to paint the city’s own dignitary, the five-year-old Prince Baltasar Carlos, and his playmate, Francisco.

It is not the first time the Prince has been painted. He has had a portrait of him by the same artist, when he was three months old, with his mother Elisabeth. But it was Francisco’s first time posing with the Prince.

A playmate of the Prince, Francisco is no child himself. From the time he was a toddler, news of his condition was carried to the palace. He is a dwarf, God’s blessed being. As soon as he uttered his first word, the court paid his family off wages which were no joke. He began life as a jester.

A feast is not necessary. Just a simple meal, says the Great Artist who believes that a full stomach leads to lethargy and lack of inspiration. In the King’s hunting lodge, where the painting is to take place, the Great Artist spends some time arranging Francisco’s pose. It is private and informal, a perfect setting to capture a venerable being, an entertainer for the kings. Francisco wears a green woollen cloak, and his white muslin shirt is teased through the collar. His fawn jacket is cut a little short at the sleeves, to emphasize the child-like wrists. Into his hands, the Great Artist shoves a pack of cards, which he has brought on his travels.

The Prince grasps his play-sword and baton, engaging in his own imaginary battles, while Francisco is being prepared. In the end, it is decided that Francisco should be sprawled like a child to accentuate both his stunted and bowed legs, and the fact that he is not only limited in stature. His gaze, penetrating yet lacking in focus, was as an inebriated adult’s. His head, unsteady and tilted, was as a tired child’s.

The jester blindly shuffles the cards, his expression vacant and intense. Is he tired? Perhaps. But the Great Artist does not judge. He is here to paint. Here is God’s venerable being. The dwarf’s open mouth drifts between smile and stupor.

Each morning Prince Baltasar Carlos plays with the dwarf, attending the posing sessions in the afternoon after the siesta. The Great Artist is intent on creating a late afternoon, late summer lighting effect. A heavy cloying scent fills the hunting lodge each afternoon. It does not take long for the Great Artist to discover that Francisco is under the influence of alcohol after a sumptuous lunch at the palace. The young Prince at his two-hour siesta also provides the dwarf opportunity to indulge in his own entertainment: women and alcohol, in his modestly flamboyant chambers. There is no being more venerable under heaven’s gaze.

Alejandra confirms the drunken vileness of the dwarf, while her creamy white thighs are wrapped around the Great Artist’s one evening in the hunting lodge where he is temporarily accommodated in the upper chambers. In his fists, he is still gripping her copper hair. He would very much like to paint her too, but that is not permitted by the King or the court. She is decorative, a glass rattle, a playmate for the playmate. The instant the Great Artist set eyes on her, he knows that she would make a subject, if not, his career.

All artists are known for are their subjects; the artist himself is as flat as a window pane, invisible until the subject is visible. The light that falls on her nose, brow bone and the M of her upper lip glows back, so startling her outline looks golden. Her magnificent chest demurely encased in silks and fine brocades, fabrics the Great Artist’s wife has never even seen, tightly conceal Aleja’s character like a wound spring, ready to pounce.

She is a poor illiterate girl, like all the others, pulled out like a weed by the King’s agents from a dense village, thick as mud with poverty, for her beauty alone. The object of education is to teach us to love what is beautiful, said Plato. An uneducated girl is teaching him what he’d never learn, the madness that is beauty. Her parents couldn’t wait to part with her for the price, a bit more handsome than the King himself, which is saying something.

There is no price for art or love.

It is the price of fear.

When he has painted the King, the Great Artist makes him someone else. Art is a mirror. It reflects what the world wants to see.

She has a caged animal’s eyes. Raw Umber with threads of Prussian Blue. She wants to escape, she says. No one knows she has left the palace at this hour to go to the hunting lodge, where the Great Artist resides while on commission. Soon I will depart, he says. She is young, she says. She can work.

The Great Artist thinks, no, she can’t work. She’s never worked. She is barely older than a child. She can’t cook or read. She has never cleaned. Never stood in a shop in a filthy apron and headscarf, bantering and talking money to a queue of customers. She can color her lips Vermillion, and play cards. She can babysit the Prince. She has no other skills. Her work consists of lying with a drunken dwarf and sometimes the King when he tires of the other flowers. They wilt too. From being toys, they become shadows, long, deep. The Great Artist has seen them, soft as ghosts, floating across marble floors, or awaiting under arches for meal times and walks in the royal gardens. That is what will happen to Aleja, maybe in as short as ten years. If she has children, they will be well cared for, until they become of age to be of service.

Sometimes they do runaway. The King carries out a search, and offers a hefty reward for anyone with information, she adds to his thoughts. When they are brought back, they are severely punished in unspeakable ways. Never, ever come back. She’s learned that.

You will get paid on the fifth day, while they get your horses ready, she plans. I will get into your carriage and wait until night. We will leave together. He looks at her. The Perfect Subject. The Great Artist can spot a wave coming.

And it is not desire. That passes.

The copper hair, the chest, the M on her cupid’s bow. This is the beginning of a movement. He can feel it. He wants her in his carriage right now, leaving the palace, to a world she does not remember even seeing as she has been here too long. Her tears fall. She stares so hard at an invisible point in the deep dark folds of the drapes, she may as well pierce them.

What will he tell his wife? Where will Alejandra live? Can he afford to rent an apartment in Seville for her from that rogue landlord he knows? It is possible. All is possible in love, they say. They do not say, all is possible in vanity. For the Great Artist knows, he is vain. That is art, and his ruin. His vanity has made him his living painting those who are also, in turn, vain.

The fifth day arrives. The painting is complete, unveiled, still raw and pungent as castor oil. The King has invited the Great Artist for a family celebratory meal while the carriages are being prepared and the packing up being carried out by servants in the hunting lodge. The Queen would like to set another date for painting her sister and her. The children play in the next room, the Prince having taken not much notice of the portrait of him and the dwarf.

Francisco Lezcano watches the meal intently from the next room where the prince and princess are playing. He moves their gold-painted jeweled wooden toy horses and carriages around, play acting with swords and painted figures. He is not considered a man nor is he a child. He really needs a drink. The Great Artist will get his fees very soon, the court officials bring the contract in and the payment. He listens until the meal is over and it is time for the children’s siesta. He knows what follows. A luxurious hour of intimacy with Alejandra while she weeps like a rusty machine.

He awaits her in his chambers.

The Great Artist wakes up after his siesta. His head and heart are pounding. He almost does not wake up. It is like being born. He sees the sun, long and low. He rises and staggers to the stables.

Night is falling. Horses sigh and grunt, their hooves making the thud-thud-thud of apples falling on gravel. Soon it will be autumn. Under the deep shade of the Kapok silk floss trees, the Great Artist examines his luggage, tools and equipment in the carriage the servants have loaded. He sees a large mound, covered by a deep patterned Rioja-colored brocade wool cape. Relieved, he calls her.

Aleja, he whispers, we are going now. We’re leaving. The mound twitches slightly.

He hears voices. Alarmed. Raised. There is movement coming and he does not know from where because his senses seem brutalized by the deep sleep. He jumps onto the carriage and cracks the whip. The horses bolt. He keeps looking over his shoulder; he’s panting and has a blinding headache. No one is following him. No men, no horses; has he imagined it all?

Something has happened. He has been drugged. He must have been. Bright lights enter his pupils like pointed blades. He remembers the Prince sword play-acting not that long ago. Still he rode, the deafening wind and the thunder of the horses’ gallop reassuring him. You’re free, Aleja, you’re free, he screams into the wind which eats up his words.

An hour passed, maybe a couple. He stops at a farm. It’s deserted.

He jumps off, hurrying to Aleja.

He flings the wine-colored wool fabric open. Under it is a deep green cloak used as a blanket. He has seen that before.

With trembling fingers he’s used to create all his masterpieces, to hold gold cutlery with which he ate like a king, and after which, to caress the most beautiful woman he has ever seen, he peels off the cloak.

That vacant and intense expression. That head, unsteady and tilted.

That gaze, penetrating yet lacking in focus.

That open mouth which drifts between smile and stupor. And that fawn jacket, cut a little short at the sleeves, to emphasize those child-like wrists.

Poison. Your fee. She.

On hearing the four words, the Great Artist knows he has been drugged and robbed. The only reason Francisco Lezcano is in the carriage is a kind of collapse, medical and final, while Aleja exerted her only strength on him in those moments after the packers have left.

The warning from God’s venerable being, and therefore God Himself, has come late, like night.

The Great Artist.

He weeps so hard he cannot find in the child-like wrist that which beats, clear as a star, pressing and true as beauty itself.

Francisco Lezcano (1638 – 40) and the Great Artist in the Court of Philip IV

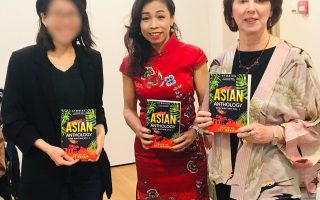

Ivy Ngeow was born and raised in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. She is the author of three novels, Overboard (Leopard Print, 2020), Cry of the Flying Rhino (Proverse Hong Kong, 2017), winner of 2016 International Proverse Prize, Heart of Glass (Unbound UK, 2018) and numerous short stories. She also writes mini lifestyle books on cooking, beauty, health and fitness. She lives in London.

was born and raised in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. She is the author of three novels, Overboard (Leopard Print, 2020), Cry of the Flying Rhino (Proverse Hong Kong, 2017), winner of 2016 International Proverse Prize, Heart of Glass (Unbound UK, 2018) and numerous short stories. She also writes mini lifestyle books on cooking, beauty, health and fitness. She lives in London.

#overboard #ivyngeow Tweet me: @ivyngeow